A Year in Spello

Many times, people tell me how much they long to live in Italy or dream of spending a year there. Often times, they'll give me a list of reasons why they can't: the kids, worries about health care, bureaucracy, etc.

Not one of those should stand in your way.

This tale will show you why; it shows how impossible dreams can become reality.

It is the journey of Michelle Damiani, acclaimed author of Il Bel Centro: A Year in the Beautiful Center. If you love Italy, this is a book you need to read.

Get this book for FREE. Become a supporter today!

Michelle's Story

It started as more of a conversational glimmer than an idea: What if we moved abroad for a year? Once uttered aloud, though, that idle wondering took hold and wrapped my husband and me in its thrall.

It’s hard to catch a free moment when you have three children, but whenever we did, we’d whisper to each other, “Big town? Or a small village?” “Somewhere we’ve been? Or someplace totally new?” “How long until we can save enough to do this?” Those moments were jolts of electricity into our lives—my first inkling into the power of dreaming.

A plan began to take shape. We quickly decided on Italy as our chosen destination since it is a country that has magnetically pulled us since before we were married. We were engaged in Tuscany and toured northern Italy for our honeymoon. Whenever time and resources permitted a vacation, our thoughts would turn to the boot.

For the sake of carefully weighing our options, we did briefly flirt with the idea of living somewhere more foreign to us, but we decided that with a family of five, just leaping across the Atlantic would be an adventure.

We’d rather not have that adventure steeped in the challenges of trying to learn a language with a completely different alphabet, struggling to get our bearings in a country we’ve never visited, or attempting to create connections among people who would be suspicious of our presence. Plus, I really like pasta.

Finally, we settled on the Umbrian village of Spello. Unlike many of the small towns we’d visited, it was vibrant and full of life. We could picture ourselves here, walking our children to school in the piazza, having a daily espresso at the bar with the laughing barista, and taking too long at the gelateria to select the perfect flavor combination.

Five years after we first pondered the question, we arrived in Spello with our three wide-eyed children, our two yowling cats, and five gargantuan suitcases. It was the beginning of an experience that even twenty more years of planning couldn’t have prepared us for.

School

It wasn’t always easy. School, in particular, presented us with more challenges than we’d anticipated. I’d heard that Italian teachers were notoriously draconian, but I had brushed that knowledge away like the light buzzing of a gnat—in part because I’m relentlessly optimistic and have a hard time picturing bad things happening (not always to my advantage) and also because I assumed that a teacher’s yelling would be confined to misbehaving children.

It never occurred to me that a teacher would mock and deride my gentle ten-year-old daughter for not turning to the appropriate page in the book quickly enough (when she was still learning her Italian numbers). And it truly never occurred to me that my five-year-old baby would be spanked by his teacher.

Those were moments when I decided that my optimism was actually distorted foolishness, and I needed to return my children back to the land of Stars and Stripes before I did them any further damage.

I’m glad I quelled that impulse to flee. Because in staying, I learned that the teacher who spanked my son was a substitute, and his regular teacher became a shining beacon of loveliness in our lives. She radiated love for our child and stands in his (and our) memory as the embodiment of cheerful kindness.

As for my daughter, she and her math teacher never warmed to each other, but my child learned the extraordinarily important lesson of not letting other people’s stuff define her. And in the meantime, she created warm and supportive friendships with girls who stood by her and loved her, despite her alien status.

In fact, it was watching all those girls appreciate my daughter that cued me into a facet of Italian culture and schooling that I would have otherwise missed—without the American imperative to be “special,” the girls didn’t compare themselves to each other and delighted in each other’s friendship with a freedom I’d never before seen.

There weren’t any Queen Bees; rather, relationships were easy, fluid, and open in a way I had thought impossible in pre-teen girls. It was as if these children knew, whether by genetics or training, how to create a sense of community.

Community

It was, in fact, that community that made our year in Spello unexpectedly extraordinary.

Maybe it was because we arrived as a family and our children were points of contact—my eldest son quickly made friends with both students and teachers (particularly his piano teacher; he received two free hours of piano instruction a week as part of his middle school education); my middle daughter took violin lessons and helped a shopkeeper with macramé; and my youngest played cards with the old men and drew pictures for the art gallery.

Or maybe it was because Spellani are, by nature, open and embracing; one friend suggested that because Spello’s beauty has put it on the tourist map (which is, frankly, less than ideal when it comes to maneuvering through a crowd of people to get to our front door), perhaps Spellani have grown to not just tolerate, but to actually appreciate, outsiders.

It also helped that I took Italian lessons from a retired schoolteacher whose family had lived in Spello since what seems to be time immemorial. We never actually drew his family tree, but the number of stories he had about life in long-ago Spello led me to believe that the roots of that tree would twine around the Roman blocks that make up the foundation of the elementary school.

In any case, he not only introduced me to the customs, folklore, and history of the region but also ordered me to view him as kin. Even when he was reprimanding me for not bundling my children in 74°F/22°C weather, his kinship was a gift.

Hospital

When my husband wound up in the hospital with a case of pneumonia, we relied on my maestro’s translation of the doctors’ race-track-worthy Italian (with a dialect that threw us, even though the hospital in Foligno is located a scant 5 kilometers from Spello) into slow, precise Italian.

It was that hospital stay which demonstrated that though there may be quirks inherent in socialized medicine—plus some peculiarly Italian features, like the requirement that patients provide their own cutlery—in general, the care given is careful, thorough, and inexpensive.

The Beauty of Spello

Even beyond this practical help, my teacher ushered us into the heartbeat of Spello. And it was once we were part of the Spellani scenery that I began to realize the beauty of our adopted home.

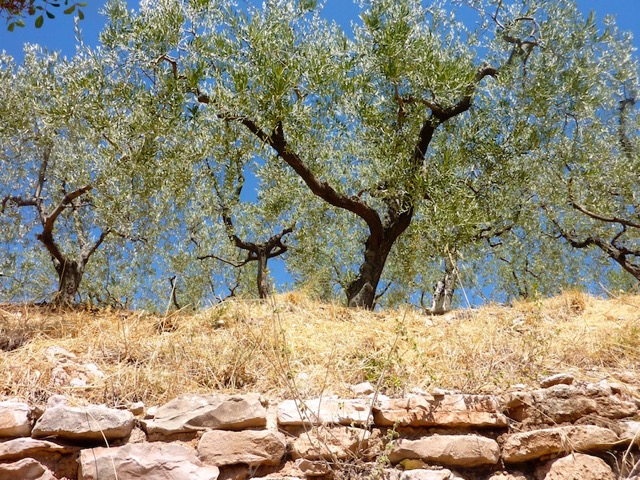

A gentle unfolding of days lived within Spello’s storied pink walls allowed me to notice the details. Not just the physical details, like the remnants of Roman writing etched into an arch, or the twisted grapevines sprawled over a sidewalk, but the details of Spellani life.

Midway through our year, I began to breathe in the deep and restorative scent of stone walls in the early morning fog. I stopped to notice the dizzying trajectories of the swallows in the afternoon. I lingered at my window, listening to the way the cadence of Italian below me swooped and lifted as the women who sit in the alley greeted passersby.

I stood barefoot with my children on the terrazza as the warm spring air stirred the hair around my temples, and we watched our neighbor’s cat assert his authority over a new kitten. I kissed the cheeks of old men in the piazza, looked into their welcoming eyes, and felt a pang of gratitude that they had moved from stranger to friend.

Infiorata (Flower Festival)

It was near the end of our year that the richness of Spello’s community became clear for us as a family. Every spring, Spello celebrates the Infiorata, a celebration of Corpus Domini in which the streets are carpeted with flowers.

I knew this before we landed, but I had no idea what it really meant. I imagined that people tossed flower petals from their yards into spontaneously scattered designs before breakfast. When in fact, the town begins preparing months in advance.

My eldest child told me that several of his classmates would miss school because they were collecting flowers in the mountains behind Spello. Those flowers were dried and arranged in boxes, waiting as breathlessly as the town itself for the day before the Infiorata.

On that Saturday, streets were patched and vacuumed, tents were lofted, and designs were pasted onto the street. Those streets were filled with townspeople, from babies to women whose hands were gnarled with age, tearing blossoms off of fresh flowers.

We were invited to join an Infiorata group that was using flowers to create a replica of Raffaelo’s Madonna and Child. Under the careful orchestration of the town baker, we worked alongside our neighbors to place blossoms onto the specified parts of the pattern, pausing for a dinner of pasta with wild asparagus, and then continuing work with one hand while the other held espresso or cake.

Every now and then, I stood to relieve my knees and watched the artists create the subtle shading of the figures with seeds and finely-chopped flowers.

The town hummed with a carnival atmosphere, as groups wandered to watch the progress in the streets, shops stayed open all night, and the air was laced with scents of pastries and coffee.

That night we felt one with Spello. Not just drifters or visitors—we belonged.

The next morning, after walking through town agape at the artistry and creativity displayed on every street, we were pulled back to our group to watch the procession of the priest along the carpets of flowers. Our neighbors welcomed us with kisses, and pressed yet more cake into our willing hands before we stood to watch the procession as part of the community.

Leaving and Returning

Leaving Spello at the end of the year was heartbreaking. And the following two years, until we could save enough money to return to Spello, were often excruciating.

But when we returned last month and climbed out of our rented Fiat to the sound of churchbells, all that accumulated tension slipped away like a tower of sand tugged by a warm wave.

Quickly, it felt like the previous two years away from Spello had been a dream.

We were welcomed back with affection—an affection that positively spilled over on our last day, when the town held a party in honor of the book I wrote about our year in Spello.

My speech at that event was, in effect, a love letter to the town that had made us one of their own. So speaking the words in Italian to the assembled crowd of people who had become as much a part of our narrative as we had become part of theirs, was one of the most moving experiences of my life. And the loud applause as I sat down was better than a stunning New York Times book review.

Living in Italy changed us. And

whenever I miss those stone alleys graced with flowers, or the

evocative scent of grilled meats over a snapping olive-wood fire, or

the easy smile of joy that marks a Spellani greeting, I remember that

I’m still connected to this place that will forever feel like home.

Michelle's wonderful book about her year in Spello is now available on Amazon - click here to be inspired.

If you enjoy my site, I'd love your support.

All you need to do is book your accommodation via this link or any of the other hotel links on the website. Whether it's for travel to Italy... or anywhere else on earth, your support means the world to us.

You'll get the best deal available, and the income helps us stay independent and keep bringing you the best of Italy.

- HOME

- Italian Stories and Albums

- Spello

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.